Mind Games: Decoding Claims of China's Brain-Disrupting Weapons Amid Scepticism

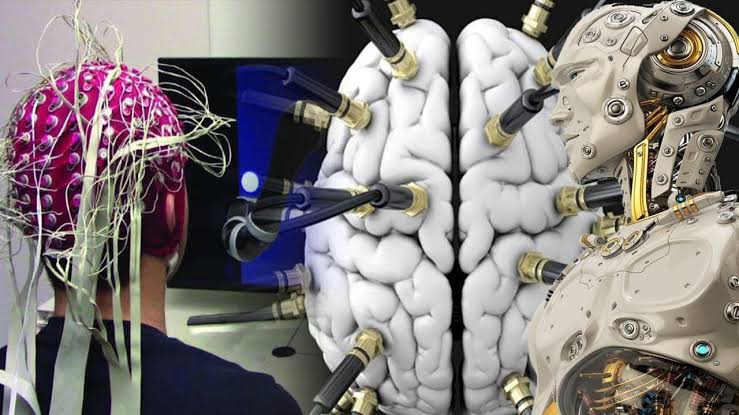

Recently, an alarming allegation has surfaced: is China, under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People's Liberation Army (PLA), developing neurostrike weapons capable of impairing the cognitive abilities of military personnel and government officials? While a report from a trio of analysts called the CCP Biothreats Initiative

Recently, an alarming allegation has surfaced: is China, under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its People's Liberation Army (PLA), developing neurostrike weapons capable of impairing the cognitive abilities of military personnel and government officials? While a report from a trio of analysts called the CCP Biothreats Initiative asserts this possibility, others within the scientific and intelligence communities express considerable doubt.

The report, titled "Enumerating, Targeting and Collapsing the Chinese Communist Party’s Neurostrike Program," alleges that China is advancing in the development of brain-disrupting weapons. The authors - a senior fellow at the National University of Singapore East Asian Institute, a former US Army microbiologist, and a former US Air Force intelligence officer - contend that microwave and directed energy weapons could potentially attack, or even control, mammalian brains, including humans.

They argue that this form of warfare, when paired with psychological tactics, forms a cornerstone of Beijing's asymmetric strategy against the United States and its Indo-Pacific allies. But is there tangible evidence to support these serious accusations? The report, despite its strategic speculations, offers little in the way of solid details about these supposed weapons or how they might operate.

This dearth of specifics has previously led to the dismissal of related claims. A two-year investigation of over 1500 "anomalous health incidents" reported by US diplomats since 2016 found no credible evidence of a foreign adversary wielding a weapon or device that could cause the symptoms, which include hearing loss, vertigo, nausea, and "brain fog." These symptoms have collectively been labeled as "Havana Syndrome," referencing its initial identification among US diplomats in Cuba.

Despite the spread of these symptoms across various US embassies, including those in China, Russia, and Germany, no clear patterns have emerged from an analysis of the syndrome. Similarly, MRI scans of the affected individuals revealed no anomalies. Consequently, seven US intelligence agencies ruled out the likelihood of a foreign attack, with no "foreign adversary" possessing a weapon capable of inducing the described health effects.

In contrast, the potential for high-power microwaves to affect human cognition, known as the Frey effect, is recognized by some in the scientific community, such as Edl Schamiloglu, a professor of electrical engineering at the University of New Mexico. However, he also notes that none of the investigations into Havana Syndrome reported associated disruptions to electrical equipment, which would be expected if such an energy source were involved.

Robert Baloh, a professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, questions the very idea of an energy weapon selectively damaging the brain. He points out that many patients reporting similar symptoms to Havana Syndrome have psychosomatic symptoms arising from stress or emotional factors, rather than external causes. Baloh suggests that Havana Syndrome could fit the criteria for a "mass psychogenic illness," also known as mass hysteria. This phenomenon is marked by a group's fear response to perceived danger, even when no actual threat exists.

The debate surrounding these alleged neurostrike weapons thus paints a picture of uncertainty. While the claims put forth by the CCP Biothreats Initiative raise significant concerns about China's potential for neuroscientific warfare, a lack of substantial evidence and skepticism from various intelligence and scientific communities challenge the veracity of these assertions. The truth remains elusive, caught in the crossfire of scientific doubt and geopolitical intrigue.